It was a gloomy Tuesday morning when we arrived at the train station in Hiroshima. After getting off the bullet train, we met our local guide and started our tour through the city. Our first location was Carp Castle, erected by Mori Terumoto, a powerful lord in feudal Japan. The carp is an important symbol in Japan and is especially popular in Hiroshima, whose baseball team is named after it. The fish stands for strength and determination, as it is famous for swimming against the current.

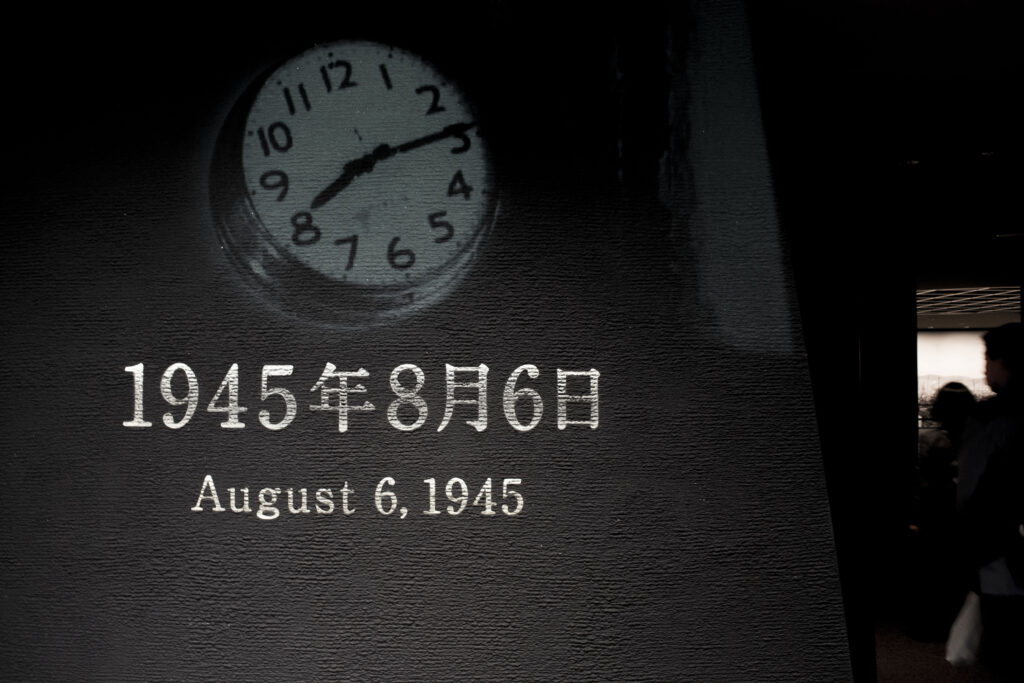

The drive to the castle brought us through a diverse and beautiful city. Hiroshima was built upon a river delta and has grown into a city with a heritage important not only to its prefecture but to all of Japan. After our tour of the castle, it became clear that many of the residents of Hiroshima are proud of their vibrant ancient history. However, as we passed by a collection of stone shrines and other historical relics, I couldn’t help but remember that they are not the original structures. Like the vast majority of the buildings in the city, they had to have been built or restored in the last 73 years. There was an elephant in the room that had to be addressed. It was the reason we were there, after all.

That was what I found to be the most powerful aspect of the museum. It wasn’t about the violence between the Americans and the Japanese. It wasn’t about governments hating each other, with one bombing the other’s territory. It was about people killing other people and how wrong that is, not just at the scale of an atomic bomb attack but on any scale. There is a unity that has been created here, at ground zero, in the hope for a denuclearized future. It’s a hope that transcends borders.

. . .

I visited Hiroshima in the months before the meeting scheduled to take place in Singapore between President Donald Trump and DPRK Leader Kim Jong-un, when this issue of denuclearization was once again a massive talking point on the world stage. The issue remains prevalent today and there are many questions still to be answered. Is it possible for humans to ever live in a world without these weapons again? Is it possible for the governments of the world to trust each other enough to stop stockpiling enough firepower to wipe entire countries off the face of the earth? I’m not sure. What I do know is that the ruins of the Hiroshima bombing still stand as proud and solemn monuments of the direction humans can take the world if they aren’t careful.

Words and images by Luke Netzley