Have you ever dreamt of stepping above the clouds?

It was a quiet morning in Emeishan, a pearlescent temple town on the western edge of the Sichuan basin. Far above the waking streets with their strolling elders and shaokao stands, the highest of the sacred Buddhist mountains cast its shadow over the world.

I woke to the calls of roosters from the courtyard where I had drowned in cheap whiskey and the cries of an electric guitar. The singers and gamblers of the night had lulled me and my companions into a trance while a baby snow leopard stalked us from below the tables. The red paper lanterns still hung in the mist.

For the uninitiated, Mount Emei takes as much as it gives. Stumbling out of bed with a pounding head and churning stomach, I would learn that lesson the hard way. My mouth croaked for water and my eyes flinched at the piercing break of day. The eastern skyline had caught fire. I imagined the climb ahead.

Mount Emei is the highest of the Four Sacred Buddhist Mountains in China, standing over ten thousand feet tall. It is also one of the most significant Buddhist landmarks in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage site that draws thousands of tourists and pilgrims alike each year, lured by its golden summit and the Guangxiang Temple, regarded by some as the first Buddhist temple ever built in China, dating back to the 1st century CE.

Nothing could have prepared us for the first hour. My companions and I were afflicted by the lack of a filling breakfast or a good night’s sleep, the late summer’s heat and humidity, and the heavy bags pulling at our shoulders as we ascended the stone. The incline was steep and the rising sun unforgiving.

Climbing higher through the lowlands and their dense forests, we came across a man with tattered clothes lying on his back beside the road. A small crowd of local children and stone workers had gathered around him, the man whose legs had been broken and his face bashed by the steps that had grown slick from the morning dew or the river rushing far below the path. The onlookers spoke into flipped-open phones and waved away our offers for help, not that there was anything we could have done.

The sunshine beamed tyrannically around us. My legs grew weary and my mind melted into the stifling air. Sweat dripped from my face, painting the stone as I took one step after the other. In the distance, a banner fluttered carelessly in the shade.

Each rest stop felt like a voyage to empyrean, a lush garden of cold water and good conversation before the inevitable return to the hellish road. Our final destination for the day was a red dot on the map labeled Xixiangchi, the “Elephants’ Washing Pool,” where the moon is said to reflect on the temple’s pools in a manner that mimics the serenity of heaven. Legend has it that the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra once bathed his steed, a white elephant, on the temple grounds.

Traversing the endless steps, the sea of clouds churning below us, my companions and I marched on into the unknown. There was a moment when we stopped on the side of the path to rest, and a figure emerged from the ghostly soup that filled the space between the trees. It was dusk and the colors across the forest floor were all washed out in blue. We watched as the man took three steps forward and stopped, then knelt to the ground, touching his forehead to the stone and rotating his hands before rising again. He repeated this process with every three steps he took until he disappeared from view. I had never seen such a powerful display of devotion. Perhaps he, too, was bound for the steps of Xixiangchi.

Before we could reach the great temple, however, a number of obstacles stood before us. First and foremost, we had yet to reach the hour-long stretch referred to as the “death climb.” Our stone trail had snaked through the mountainous landscape, the mists rising and falling around us, until we slowed to a halt before a collection of steps spiraling boundlessly into the sky above. We knew this was it.

As my companions and I ascended the cliffside, my legs began to burn as they had done at the start. We had been hiking since daybreak and our bodies were ailed by dehydration and fatigue. I paused to catch my breath and caught sight of a distant mountaineer with a long bamboo stick. I assumed the cane was meant to aid his climb. It wasn't. During the ascent, I began to notice signs on the trail that warned of onslaughts from militant monkey gangs.

The first attack came moments later. A massive Tibetan macaque jumped onto the trail between myself and two others. It leapt towards us, teeth flashing, then jolted atop one of the men. After the thief had been shaken from my companion’s back, it escaped into the underbrush with a stolen bottle as its reward. Had it taken his backpack, he would have lost his wallet, passport, and visa.

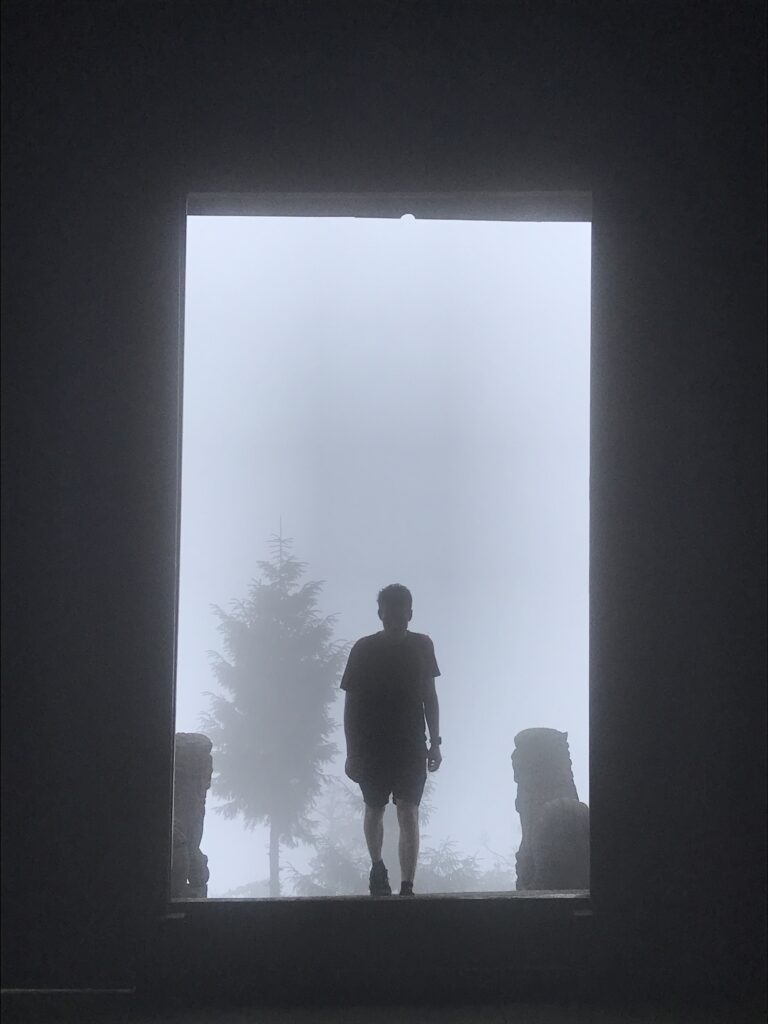

Shadows followed us as we moved through the clouds until we came across an old wooden structure. At long last, we had reached the foot of Xixiangchi. We were the first to arrive at the temple, which looked abandoned from the outside. There were no signs of life besides the silhouettes that lurked in the distance.

Visibility was low and the oxblood temple complex felt like a maze of empty alleyways, incense-filled prayer rooms, and marble courtyards. It was difficult to discern the statues from macaques. We held our newfound bamboo sticks aloft, primed and ready.

Once we regrouped with the others on the temple steps, we raced into our bunk room to avoid the oncoming assailants. Dozens of them crept outside our windows trying to find a way in. Thankfully, they never did and we were able to safely enjoy our dinner.

On that ridge above the clouds, I watched the last monk disappear through the temple doorway. We could hear the whispers of the world caught on the wayward wind as the moon loomed among the tapestry of stars. Somewhere far above, I imagined the golden summit shining in the night.

At dawn we woke to the sound of screams as the monkeys had evidently taken another sacrifice just outside our door. We could hear their footsteps on the metal roof above us like rain in a thunderstorm. With bamboo sticks raised and heartbeats shaking our chests, my companions and I left the comfort of the room. Although some monkeys would recoil at the sight of our raised sticks, some were indifferent. Those were the ones that worried us the most.

We left the temple grounds far behind us and made our way higher into the mountains, further into enemy territory, pushing our bodies to the limit, sweating waterfalls, and chatting away. Morale was high until we reached the bus stop and, soon after, the entrance to the summit's cable car. This convergence nearly broke my spirit.

Typically tourists from across the country will take a bus and a cable car to reach the golden summit of Mount Emei, bypassing the old stone pathway with its steep cliffs, cloud forests, oxblood monasteries and monkey attacks. Our path had now met with theirs, and a flood of bodies surged around us. They gorged themselves with food, took photographs of fat monkeys they had just fed, and threw used tissues into the forest. As my companions and I struggled up the steep steps, the final push of our day-and-a-half-long journey, we felt the stares, gawks, and laughs thrown our way.

As sweaty travelers, set apart by the visual cues of race and the aftermath of fifteen hours of hiking with little food and even less sleep, we were a laughing stock for many of the groups we passed. It was one of the rudest displays of humanity I had ever seen. I was disgusted by the complete and utter lack of respect shown for other people and the surrounding natural landscape. The spoiled bodies, some of which were being lifted up the mountain on the backs of local elders, had no idea what we had seen or felt. How cold a world was this, one that had no understanding, only comfortable ignorance. In the midst of it all, my thoughts returned to the pilgrim of the prior night. That man had traversed the entire mountain without belongings or burden. I wonder how he felt, seeing all this.

There were, of course, some nice passerbys who greeted us and smiled, asking how tired we were or stopping us for a photo. I wasn't certain of the intent behind wanting to take our photograph, but I had little energy left to mull it over. We had become caught in a tourist trap, a cesspool of human indifference. In that noisy place, I felt far from home.

Upon reaching the summit, I collapsed by a stone wall in front of Mount Emei's giant golden spire. The sun began to shine through the clouds and the monument gleamed in the afternoon light. I exhaled and smiled, reflecting on how far I had come and what I had experienced since beginning the climb. Mount Emei gives as much as it takes.

The summit and its spire were overrun with tourists, as expected, and portrait photographers screamed through loudspeakers into the crowd, but I was at ease. It had been a long day and I was happy to close my eyes and breathe in the cool mountain air. It was a moment I’ll never forget. I walked around the summit and enjoyed the pleasant weather and the view that stretched into infinity. Afterward, I rejoined my fellow travelers and descended the mountain as a dark yellow haze set in on the horizon, and the darkness swallowed us whole.

Signing off from the evening train from Emeishan to Chengdu,

25/08/19